THE STORY OF THE RED CROSS PEARLS

/This pearl necklace is one of more than 100 items created with the donations of 3,597 single pearls by “women of the empire” to benefit the Red Cross immediately after WW1. Aristocrats gave family heirlooms. At least one “ordinary” family gave a single pearl to represent a dead soldier. Firms such as Garrard and Tiffany made them into necklaces, scarf pins and rings.

In February 1918, when the First World War was still being bitterly fought, prominent society member Lady Northcliffe conceived an idea to help raise funds for the British Red Cross. Using her husband’s newspapers, The Times and the Daily Mail, she ran a campaign to collect enough pearls to create a necklace, intending to raffle the piece to raise money. The campaign captured the public’s imagination. Over the next nine months nearly 4,000 pearls poured in from around the world. Pearls were donated in tribute to lost brothers, husbands and sons, and groups of women came together to contribute one pearl on behalf of their communities. Those donated ranged from priceless heirlooms –one had survived the sinking of the Titanic – to imperfect yet treasured trinkets.

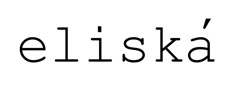

The Red Cross Pearl Appeal came to completion at the same time as the Armistice in 1918. The auction of the 41 necklaces made of donated pearls at Christie’s was one of the first post-war acts of remembrance.

Committee members for the pearl-sale scheme included royalty and duchessery, a cache of Curzons, the odd Sassoon, the Dowager Marchioness of Londonderry, various Vicountesses, and a lot of Ladies including one called Tree. Patronesses included Lady Inchiquin, The Countess of Rocksavage, the Countess of Sandwich, The Lady Bertha Dawkins, and the Duchess of Buccleuch.

The armistice changed the situation for the Red Cross Pearl appeal as well as the women who had given to it. In the changed circumstances it was important to keep the public interested in the fate of the pearls if they were to make as much money as possible for wounded soldiers returning from the war. On 25 November 1918, Princess Victoria and Lady Northcliffe sent out a letter to local and national papers explaining that the Red Cross’ need for funds was as great as ever.

The pearls now became part of one of the first post-war acts of remembrance when they were on display for three days at Christie’s King Street salerooms. There was a private viewing on 16 December where many of the visitors were women wearing their own magnificent pearls. But even they looked wistfully at some of the Red Cross Necklaces.

Admission to see the jewels was free on 17 and 18 December to make sure that the pearls could be seen by as many people as possible. By 10am on the opening day crowds were eagerly waiting outside the doors of Christie’s. The Queen newspaper wrote: “The thoroughfare was literally besieged: people who had never been in a crowd before waited and jostled with more or less good humour.” Within the first hour, 300 people inspected the pearls and throughout the rest of the day the crowd was never less than three deep around the showcases. The pearls were simply displayed in sombre, oblong black boxes. Prospective buyers asked saleroom officials to take out the necklaces so that they could examine them. Schoolgirls back for the Christmas holidays admired the “young” necklaces made of smaller pearls. However, nearly everyone was speculating about how much money Lot No. 101 the finest pearl necklace, with the Norbury diamond clasp, would make. One lady said:

“Whatever it fetches will not matter to the buyer (…) It will be historic as the jewels of Marie Antoinette; it will be an heirloom more famed than the Hope diamond. Other pearls come for the sea. These pearls came from human hearts and human tenderness and gratitude will run up their purchase price.”

The first day was busy, the second day was even more crowded. Soon after 10 in the morning the queue became so long that it wound around the outer room and stretched down the stairs across Christie’s reception hall and out into the street. The crowds continued all day long. On the final day the numbers were greater than ever and included people of every rank in life. Serviceman, home on leave, and their wives regarded the collection as one of the sights of the town.

On the day of the Pearl Necklace Auction itself, another important event was taking place in London. At 1pm on Thursday 19 December 1918, Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig and his generals arrived in London for a victory parade. Escorted by a fleet of aeroplanes, they had travelled from Dover by special train to Charing Cross Station where they were greeted by the past and present prime ministers, Asquith and Lloyd George. They then travelled through the capital to lunch with the king and queen at Buckingham Palace. Thousands of people lined the route and, as the carriages passed, those standing on balconies showered flowers on the victors.

The clamour had hardly died down before some member of the patriotic crowd rushed off to Christie’s for the Red Cross Auction. It was only a short walk from Haig’s parade to Christie’s in King Street. As supporter of the Red Cross gathered in the auction house’s impressive red-walled saleroom beneath historic portraits and paintings, there were many more women present than at most sales. Many members of the Red Cross committee were there, hoping that all their hard work would now pay off.

When the auction began at 1.30pm the atmosphere at Christie’s was highly charged as the auctioneer, William Burn Anderson, entered the Chippendale rostrum. Antique ivory-headed hammer in his hand, he addressed the crowded room explaining that previous Red Cross sales had been held under the clouds of a terrible war, while the present sale was taking place after the great and glorious victory of the Allies. The cessation of hostilities did not mean that the Red Cross “work was finished – far from it.” They still needed money to tend to the wounded, and he appealed to his audience to keep that thought in their minds as they bid for the pearls. He added that those who bought the jewels would receive “something which is not only of intrinsic value, but also of considerable historic interest for the Red Cross Pearls have become historic.”

When the first lot, a brilliant pave ring, was put up, Mr Anderson read a letter which he had received that morning from the entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sir Francis Trippel. Offering £1,000 for the first four lots, he wrote that if they fell to him they should be put up for auction again, as he only wished to give, not to buy. His letter gave advice to other bidders: “Give till your sides ache, so that the financial success of the sale may be worthy of the Red Cross, the most deserving and the most humane of war charities.”

Before the forty-one pearl necklaces were auctioned there was the sale of other pearl jewellery, including earrings, pearl pins, brooches and rings. But the real excitement at the December 1918 sale began when the pearl necklaces were auctioned. At 3.30pm there was a flutter of anticipation as Lot 95, the first of the strings was brought out and shown to the audience. It sold for £2,200. The tension increased and there was a sense of drama as the lights went up and Mr Anderson introduced “the necklace of necklaces”, Lot 101, the most perfect pearls with the Norbury diamond clasp. The first bid was £20,000 then, with his encouraging smile, the auctioneer looked for nods around the room. Bids rose in steps of £500 until the necklace sold to the jeweller, Mr Carrington Smith for £22,000.

Sadly this merriment belied a tragic reality. With aviation then in its infancy and crashes common, well over 20 trainees lost their lives at Beaulieu during the war and 19 of them were buried in the churchyard at East Boldre. Alice Shrubb’s gift of a pearl commemorated all their brief but spirited lives.

Thanks to dedicated provincial women like her, the pearl appeal spread across the whole country. In the counties it was headed by the high sheriffs’ wives, and in the cities by women like Birmingham’s lady mayoress Mrs Brooks, who announced in the local newspaper that she was ‘at home’ at the Council House to receive pearls.

Those given ranged in value from one worth just a few shillings, sent from a country vicarage, to a pearl of great price from a stately home.

Plenty came with accompanying messages. The feelings of many bereaved mothers were summed up by Edith Fielden of Twickenham, whose 19-year-old son Granville was killed at the Battle of Ypres in April 1915. ‘It is not a perfect pearl, but it is the only one I have,’ she wrote. ‘I send it in memory of a pearl beyond all price already given, my only son.’

There were hundreds more messages ‘in memory of my beloved son’, and the fact that many of the fallen were fresh-faced youths just out of school was emphasised in one gift from ‘a mother and sister in memory of two boys’.

By October 1918, the appeal had garnered nearly 4,000 pearls, enough to make not one but 41 necklaces. As it had begun when Britain was threatened with defeat, Lady Northcliffe and her committee thought it fitting it should end as the country was on the point of victory.

The British Red Cross is reviving its Pearls For Life Appeal to help support people in crisis throughout the world, to mark 100 years since the original campaign changed lives in the wake of World War I.

The charity is calling on people across the UK to show their support for the appeal by donating an item of jewellery, to be auctioned by Christie’s. To find out more, or to give to the appeal, email: pearls@redcross.org.uk.

Donations will go towards the British Red Cross’s life-saving work around the world.

Its projects include helping women who’ve lost their husbands in conflict gain the skills to support their families, establishing rest centres, providing social support and first aid, and working with the emergency services to help people when tragedy strikes.

In those last weeks, it was decided every necklace should have a clasp to hold the pearls together. Nearly 50 rubies were donated for this. A Mrs Hewitt sent one in memory of her husband, Rifleman F. J. Hewitt, with the message: ‘More precious than rubies to his wife.’

Five came from Frances Parker, sister of Lord Kitchener. He was Secretary of State for War until the fateful day in 1916 when he, his staff and 643 sailors on HMS Hampshire were drowned after its holing by a German mine off the Orkneys.

The rubies were accompanied by three pearls, ‘one for Ferby, one for little Marion and one from little Pet Evie’, all the names of family pets.

As this suggested, the Kitchener family were devoted to animals. The Field Marshal himself was fond of the gun dogs he named Aim, Fire, Bang, Miss and Damn, and his family were determined the tender side of the heroic figure should be remembered.

Once the pearls had been made up into necklaces, Lady Northcliffe’s committee faced the problem of what to do with them. One option was to offer them as prizes in a national raffle.

This would be egalitarian and lucrative, raising large amounts of money for the Red Cross at a time when it was sorely needed. But attempts to get a special exemption to the prevailing anti-gambling laws through Parliament were blocked by a powerful lobby supported by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Eventually, it was decided an auction of the pearls should be held at Christie’s on December 19, little more than a month after the signing of the Armistice. The preview was one of the first post-war acts of remembrance, attracting crowds which queued out into the street.

Behind each exhibit was an emotive tale, and none more so than the three pearls donated by a Lilian Kekewich of East Grinstead, Sussex. Each stood for one of the sons she had lost in the war.

Like the other donors, Mrs Kekewich could at least comfort herself that her gift was not in vain. The sale raised £94,044 overall — £5 million at today’s values. To put this achievement into perspective, it cost £9,585 (£500,000 today) to run all the Red Cross convalescent homes in France and Belgium from October 1918 to December 1919.

As for the pearls themselves, many of their 21st-century owners may not know the poignant history of the strands they wear.